Sarah R. Kyle, Associate Professor of Humanities, University of Central Oklahoma, has just published a book Medicine & Humanism in Late Medieval Italy: the Carrara Herbal in Padua (Routledge 2016). For a discount code, see Routledge brochure pdf

Here is her story about her encounter with the manuscript.

The day the Carrara Herbal arrived at my desk at the British Library I felt like I was opening Pandora’s Box. After all my research, all my grant applications, all the hoops and puzzles to see such rare books, I was finally here – and, now, emerging from its large but unremarkable storage box, so was the book: what would I find inside?

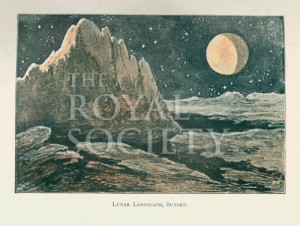

Fig. 1. Anonymous, Frontispiece with Carrara heraldry and “Citron” (Citrus medica, L., citron tree), Carrara Herbal, London, British Library, Egerton 2020, f. 4r, 35 × 24 cm, gouache on vellum, Padua, ca. 1390–1400. Copyright © The British Library Board

The Carrara Herbal is a late fourteenth-century illustrated manuscript of “materia medica” (medicinal substances) commissioned by the last lord of Padua, Francesco II da Carrara (d. 1406). The artist of the unfinished but extraordinary illustrative cycle is unknown. The manuscript contains a translation into Paduan dialect of a Latin version of an Arabic compilation of information about “simples,” singular medicinal substances from the “three kingdoms of nature” (plants, animals, and minerals), and their therapeutic uses.

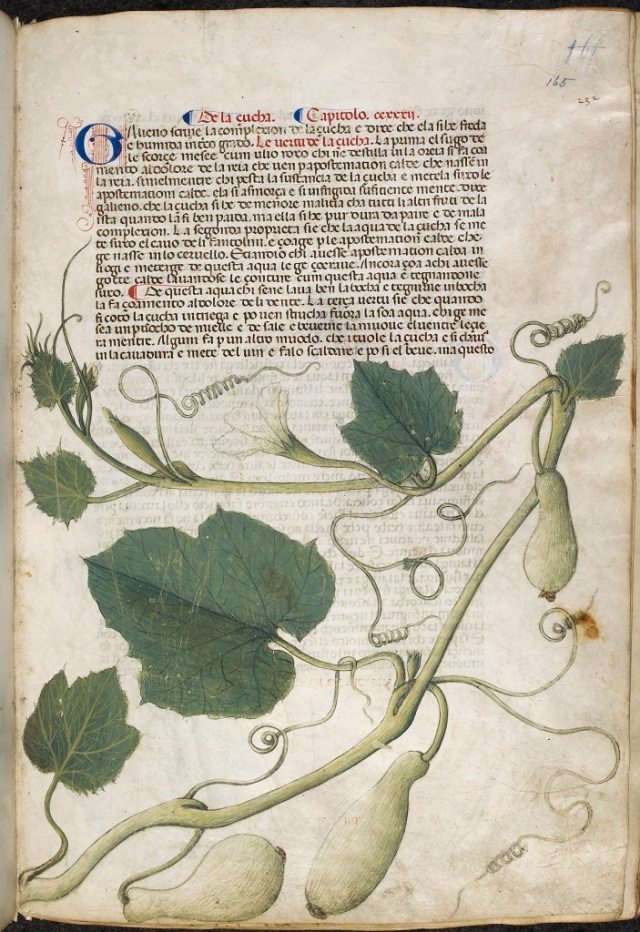

Broken into several parts, the manuscript’s text is formulaic; each entry (or “chapter”) includes an illustration of the medicinal substance in question (or leaves a space for one), and the text follows a pattern in its presentation of information about the drug and its therapeutic applications. The scribe left a large, blank space within each entry (some of which are several pages in length) for an accompanying illustration of the entry’s substance; yet only the “herbal” section, the section devoted to plant medicines, is illustrated – and it is incomplete. The plant images, while composed by a single artist, vary in style and composition, from the starkly schematic to the resoundingly realistic and to complex combinations of the two. The unknown artist evoked both illustrative traditions and innovations in his representations of plants in gouache (a kind of watercolour paint) on the manuscript’s vellum pages. I was intrigued by why he would choose to represent the plants in these ways, and why so many contemporary scholars had neglected the stylised or schematic plant images in their analyses of this manuscript.

As I scrutinised the diversity of imagery and grappled with the idiosyncrasies of abbreviated Paduan dialect, I was struck by the deeply physical process of reading and studying the text – an observation that came to inform the central argument in my book. The Carrara Herbal was developed to cultivate a particular reading-experience, one that captured the readers at every turn – distracting their focus from the text or from the images with sketches of faces that peek out above the names of cited medical authorities (as though Dioscorides or Galen himself had popped in for a lecture!). These memorable “breaks” in the text and the different styles of images that themselves puncture the flow of words – sometimes growing up from behind or encircling the text block – deny passive reception of the book’s content and continuously remind readers of their engagement in the act of reading this very book. By reminding the reader of the book as an object tied the process of reading, the Herbal ties the reader – inextricably – to its owner, the lord of Padua, and to the patterns of artistic and intellectual patronage engaged by his family over the course of their rule of the city during the fourteenth century.

Fig. 2. Fig. 2. Anonymous, “Çucha” (Cucurbita lagenaria L., bottle gourd), Carrara Herbal, London, British Library, Egerton 2020, f. 165r, 35 × 24 cm, gouache on vellum, Padua, ca. 1390–1400 Copyright © The British Library Boar

The Carrara lords supported the University of Padua, luring prominent scholars away from the competing schools at Bologna, and courted humanists, especially Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374) and Pier Paolo Vergerio (1370–1344/45), to settle and teach in Padua. The Carrara Herbal’s textual content connects it to the growing interest in the “new” Arabic medicine being taught at the university, while its imagery ties it to the patterns of illustrated book collection and of portraiture engaged by Carrara court, and to humanistic ideas about the moral value of reading, art, and nature. I argue that the Carrara Herbal, in creating and cultivating the reading experience that it does, enabled Francesco to bring together several threads of the Carrara family patronage strategy, locating (and promoting) himself at its nexus, as a progressive leader – a “physician prince” of Padua.

Perhaps with the exception of the advocates at the Material Collective, art historians often don’t get to talk about their personal, subjective experiences of art. We analyse the form of a work of art and dissect its content with a critical eye. We consider questions of facture or audience reception and we study – among other things – why and how the works were made, perceived, and understood. But before we can do any of that work, we must experience the art itself – we must reckon with our own subjective engagement and how, in the case of this illustrated book, the visual and textual rhetorics manipulate us as viewers and readers. I recognised and understood this truth, fundamentally, the day I opened the Carrara Herbal and started to read, and since then it has informed my thinking about the production and historical reception of this book and others like it. The form and content of the manuscript, in its text and its imagery, shape the readers’ experience of the book as a whole, continually reminding us of the book’s physical presence.

Visitors to this site might have or know of brilliant undergraduates or Master’s students looking for a funded PhD position. ‘Hans Sloane’s Books: an early Enlightenment library and its material relationships’ is funded by the AHRC (UK), and is a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership between Queen Mary (University of London) and the British Library. For further details, please see:

Visitors to this site might have or know of brilliant undergraduates or Master’s students looking for a funded PhD position. ‘Hans Sloane’s Books: an early Enlightenment library and its material relationships’ is funded by the AHRC (UK), and is a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership between Queen Mary (University of London) and the British Library. For further details, please see:

![Joannes Viringus compares the Fabrica with the Epitome, p. 249 [349]. © Bibliothèque municipale de Boulogne-sur-Mer.](https://picturingscience.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/5-boulogne.jpg?w=640&h=480)